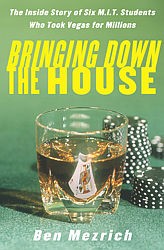

Bringing Down the House

Bringing Down the House

is not a tutorial on how to beat the house playing blackjack,

but the story of how smart people worked together to play the

casinos' game, on their own turf, and win. The narrative

benefits greatly from author Ben Mezrich's experience as a

novelist, showing how an MIT student went from working part-time

in a chemistry lab between classes to playing blackjack with

tens of thousands of dollars at stake in a single hand.

Bringing Down the House

is not a tutorial on how to beat the house playing blackjack,

but the story of how smart people worked together to play the

casinos' game, on their own turf, and win. The narrative

benefits greatly from author Ben Mezrich's experience as a

novelist, showing how an MIT student went from working part-time

in a chemistry lab between classes to playing blackjack with

tens of thousands of dollars at stake in a single hand.

Even though the book is not a tutorial, it does discuss in surprising detail the strategy behind counting cards. Much of the work on outsmarting blackjack can be traced back to a 1962 book, Beat the Dealer, where MIT professor Ed Thorp showed that blackjack is a game that can be beaten. The fundamental issue in card counting is that blackjack is a game of continuous probability, which is to say that the result of one hand will have an impact on the probability of the next. In blackjack, if an ace of spades is played, it cannot be played again in the same shoe. (Even in multi-deck shoes, the same is true; a six-deck shoe will simply have six of each card instead of one.) This varies dramatically from a game like craps, where one roll of the dice has no impact on the next roll of the dice.

Card counting is not illegal but casinos don't like it because a card counter is not gambling: he knows that in the long run he will win. This is actually the same position that the house is in with all other games, and even in blackjack where the players are not counting cards. Casinos can't call the police, but they can eject card counters, and tell them that they're not allowed to come back—just like any other private establishment that is otherwise open to the public.

Working in teams, card counters can disguise the fact that they are counting cards. Someone simply watches the table—perhaps even by playing with minimum bets—and makes a gesture to call in a teammate when the odds are good. Through some previously-devised code, smalltalk that goes around the table will pass the count—a number that indicates the probability of favorable cards coming up. Telling the dealer or a random player, “I hope my sister remembers to feed my cat,” for example, would tell a teammate who just joined the table that the score is +9 (cats have nine lives). The teammates never regard each other or interact more than two random strangers would. The end result is that the people with the real money only play when the odds are in their favor, then they play big, and win big.

As a solution to a game, card counting interests me. No way could I make a living from playing blackjack, though. My real problem is that even though you can win more money than you lose, as well as cover expenses for such things as travel, you're not really making money. A lot of people have the crazy notion that making money is the same thing as getting paid. I don't share this view: my objective in work is not just to get paid, but to create value. A good exchange of goods or services and money should ultimately create wealth; both buyer and seller are better off at the end of the exchange. This is how economies grow, and how an economy that functions well benefits everyone.

Blackjack is a zero-sum game: for a player to take a dollar, the house must lose a dollar. No value is created in the transaction. (Casinos, of course, will tell you that the reverse is not true: although players as a group lose more than they win, the difference is a premium for provision of a service: entertainment.) If one is going to engage in commerce, it seems more agreeable to my sensibilities to create some real, sustainable value in the process.

All of that said, Bringing Down the House is a thrilling story, presented well, on an interesting theme.